2.

From Domains to Kaleidoscopes: Thinking about A Teaching Self

“We spend half our waking lives at work, but too many of us live half-lives while we are there” (Palmer, vi).

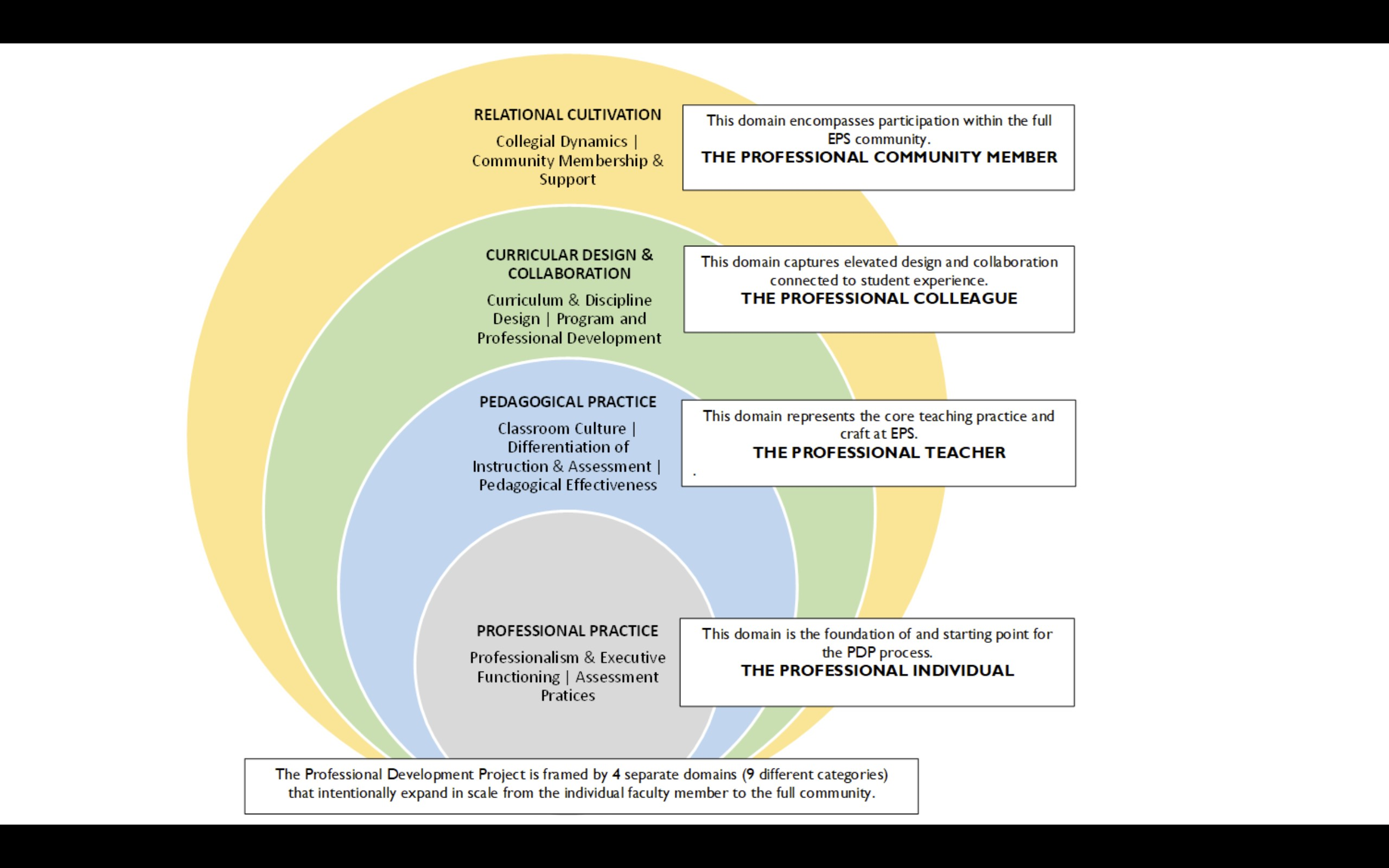

The Spheres

In the orbiting spheres of the PDP model, the inner, gray-colored sphere indicates professional practice, one domain of four, that focuses on assessment and ‘executive functioning.’ From here, the spheres expand to the domains of pedagogical practice, then curricular design (a domain reserved for certain levels of candidates) and then the final outer limit extends to relational cultivation—the pale-yellow sphere.

Yet, in the schedule of meetings, reflection begins with the relational cultivation sphere, the pale-yellow measure of a candidate’s ability to participate in the school community and partner with colleagues. While the spheres dictate a focus on the outer strata first (the relational), I can’t adequately consider relationships without first considering my inner sphere.

Better still, the model itself, which arbitrarily sets out categories, domains, and indicators betrays the obvious ways in which these spheres are always bending, spinning, contracting, and expanding –how the color-codedness of models inevitably blur, bleed, and fade.

As I hold up the spheres of development, I am reminded of my grandfather and his homemade kaleidoscopes—the one he gave me still nestled in my antique chest. I delight now as I did then at the colors pixelating and fragmenting with each subtle turn, bursting into infinite mandalas. In my approach, this morning, I feel more connected to the kaleidoscopic model of development, fragmented and fleeting, than the concentric sphere model. As I look through the spinning pixels of practice, maybe I might see where I still dance in my practice, where I pause, laugh, and breathe.

As such, rather than turn outward at the farthest perimeters of the PDP spheres, I want to turn inward, towards the self as a center from which all the other spheres emanate. Not only is a teacher identity criteria absent in the current model, it is also largely absent in discussions about professional practice. Rarely do we take time to consider ourselves or the way we carry the self into everything we do in the classroom.

In my creative writing classes, to introduce the idea of writing from the heart and demonstrate the difference between expressivist rather than expository writing genres, we use an image from G. Lynn Nelson’s book Writing and Being. He borrows the idea of a petroglyph to create a vision of a heart filled with a spiral to capture his sense of how personal writing begins from within a spiral of thoughts, feelings, experiences, and beliefs. Out of this spiral, a piece of authentic personal writing might emerge, but it first requires an inward turn.

Likewise, here, I turn inward first, in the writing, reflection, and the view of my teaching life. Along with Nelon’s petroglyph, I employ the kaleidoscope to represent an inner circle out of which the other spheres amplify. Looking through the kaleidoscope of the self, the inner mirrors do not provide a faithful reflection, rather they create the magic and mystery of pixelated colors, always rotating, always shifting, and merging into one another. With each turn, some new design appears.

Below, I offer the following fragments, the various shades of my thinking about relationship, which also includes my thinking about a number of coexisting people, places, institutions, and ideas, as a model for thinking about how the teaching self interacts with classrooms, colleagues, and institutions in fascinating, complicated, and sometimes unquantifiable ways.

Pixelations of a Teaching Philosophy

For the first turn into the rotating depths of my teaching self, I step back to consider two questions that might cradle my thinking. The first question I remember from one of my education professors, something like a philosophical inquiry or teaching koan that we returned to over and over throughout the semester, a single hand clapping in the woods where a tree has fallen for (no)(some)one to hear: What’s my job?

I love the Zen-like mystery and openness of this inquiry because the vagueness of ‘my job’ somehow permeates all of these spheres at once, the metaphorical hand that turns the kaleidoscope of my profession. It implicitly asks questions about the boundaries of responsibility, the limitations of influence. The question helps clarify, distill, and problematize certain assumptions about where the teaching life begins and ends. At another level, the question invites me to articulate something specific about teaching English, something particular to my philosophy of teaching literature.

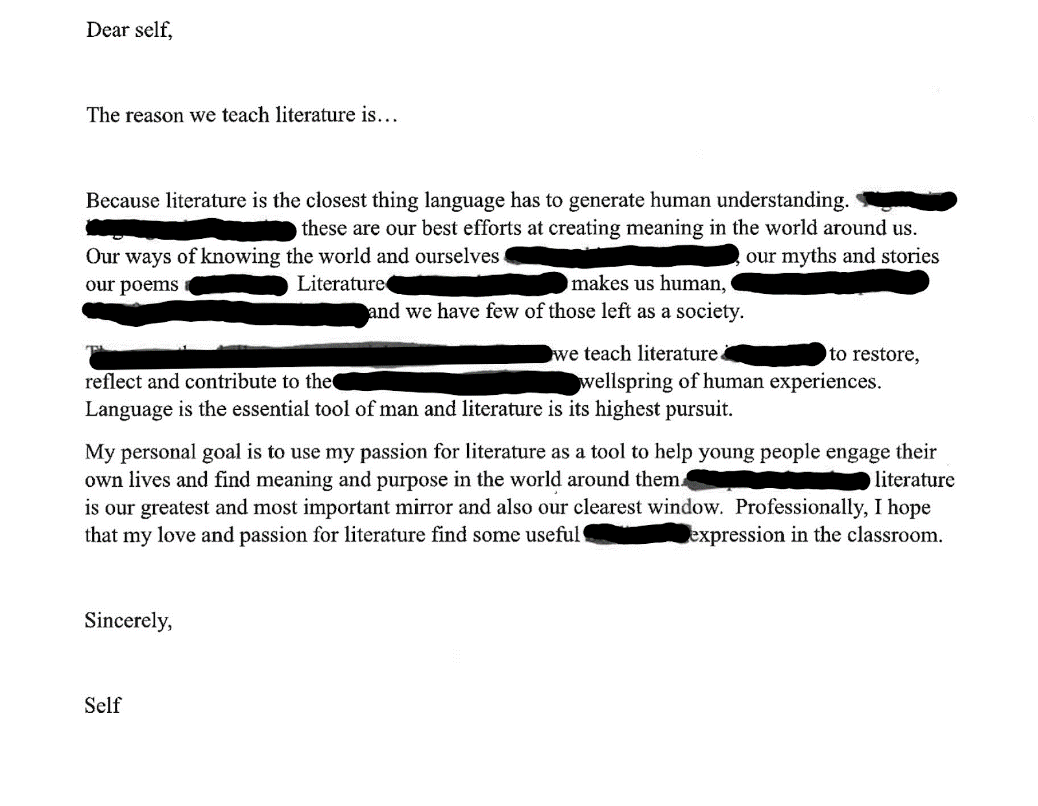

Therefore, I hope to sit with this inquiry through my writing. In digging through some old archives from my teaching program, I located a version of an old (perhaps first) version of a teaching philosophy framed as a letter to my self (1-21-14), with the prompt, “The reason we teach literature is…”

I have included a redacted version below to save myself the embarrassment at its hurried and carless composition, while still highlighting some of my early idealisms and ambitions.

Even beneath the veil of redaction, I loathe to publish this crude little, decade-old idealism. And yet, I find tremendous value in re-reading my first, clumsy attempt to formulate my answer to the question, “What’s my job” or to set out in writing the ambitions of my teaching life, to first begin, as it were, a relationship with my teaching self or a construction of my teaching identity. In my encounter with this past, discoursal self (the self constructed on the page), I can grow down deeply into the fragments of experience, writing, and reflection that underlie my current practices.

In the sparkle and tinsel of this pre-service teaching optimism, I locate a few enduring ideas. I still believe, or maybe believe even more strongly, that the space and activity of the literature classroom accesses and nurtures humanity in immeasurable ways, that our literature and language most closely touch and provide a vehicle for the activity/experience of being. Here too, I feel confirmed in the importance of and my commitment to my work (my job) to facilitate experiences and create space for that experience for students.

The other reason I include the artifact of this earliest permutation of a teaching philosophy is for the mirrors and windows formulation of teaching literature—a popular idea I somehow borrowed or latched onto sometime during these fledgling years when I attended classes, waited tables, and drank copious amounts of caffeine. To review, the windows/mirrors philosophy of teaching English posits an idea of being either mirrored/represented (seeing yourself) or windowed/seeing into the lives of others (presumably those from outside your immediate identity). At the time of this note, I accepted this view without apology or pause. Now, I am deeply dissatisfied with the passivity and neutrality of windows and mirrors. I reject the implication that transformative pedagogy can come simply through greater representation or more sympathetic looking. But if not mirrored or windowed, then how might transformation occur?

Toward a Critical Perspective

Hopefully, in the face of perpetual social crisis, the need for change goes without saying. The question remains, however, whether strategies to address global collapse can come from within existing structures or whether they demand an ability to imagine new structures/strategies.

Some educators have come to label this disposition (the belief that education should serve social changes) as transformative or critical pedagogies. Ultimately, as educators, if you care about the world, you must inevitably arrive at this impasse. From here, two possibilities emerge: the position of doing the most good in the limited scope of a classroom within existing conditions or the belief that the actual work of schools should be to re-imagine or abolish the structures that perpetuate suffering. For the latter, all roads sort of lead back to Paulo Freire.

Without going into much detail, Paulo Freire, the Brazilian educator, serves as the centerpiece to a larger philosophy of education called critical pedagogy—outlined and proliferated in the seminal text The Pedagogy of the Oppressed. While articulated and elaborated in a number of fascinating ways, Freire and critical pedagogies borrow heavily from Marxism and the possibility for education/literacy as a vehicle for social transformation, empowering those who are disempowered. Freire distilled his view as ‘reading the word to read the world’—that literacy education should facilitate social change. I might also note that EPS has a version of this idea in its mission statement: Inspiring students to create a better world.

By the time I arrived in Seattle to begin my current teaching position, I had developed a teaching philosophy with pretty obvious critical influences. I felt excited to engage with students who seemed not only receptive but deeply informed in their own commitments to social justice. In fact, the average EPS student probably possesses a political sensibility more advanced than my own, or at least they have internalized highly developed languages and gestures of social justice.

Somehow in those first two years, I started to wonder about the effectiveness of consciousness raising, of windows and mirrors, of feeling good about our sophisticated liberal sensibility, about the skill and effectiveness with which we talked about and wrote about inequity, injustice, and even the ravages of capitalism. Slowly our ‘critical’ /social justice-oriented work began to feel at odds with the remoteness and insularity of our Kirkland office park bubble. The few times I poked this nerve with students or colleagues, things got messy and complicated.

In some ways, teaching and becoming expert in the languages of social justice in an elite school context might even perpetuate suffering and uphold dominating structures. As elite students acquire and master the languages and gestures of social justice (using them to both demonstrate academic achievement or otherwise inform their college applications) they gain a currency for the windows and mirrors of identity while still benefiting from a system that continues to create economic disparity. While the view from the mirrors of TALI and TMAC looks pretty good, as I drive back across the 520 bridge, the view out the window of my car looks startling, if not apocalyptic.

Partly out of utter defeat and partly because students began to resent my calling attention to these inconsistencies, I eventually softened or quieted my convictions in favor of a less demanding approach, one in which we limit the activities of the classroom to how we talk and think about the world without much attention to how we act in the world.

A later version of my teaching philosophy helps to outline and capture my attempts to reconcile this dissonance between the ideal of critical praxis and the realities of the unique particularity of preparatory school contexts, which inherently depend on existing structures and not subverting structures:

Once I began to accept the obviously transformative possibility for the classroom, a new sense of responsibility took hold. Out of that newfound understanding, movement necessarily follows: a spark, a catalyst. Personally, that movement became an impulse to empower students, to inspire—and yet, I return to the same lesson I learned three years ago—about my own limitations in the classroom, about the powerful societal forces which deter critical consciousness. I’m reminded of moving from an inspirational posture to a respirational one, from trying to inspire to stepping back and giving students room to breathe for themselves.

Again, I find myself searching for balance. If radical pedagogy claims to engender critical consciousness (a heightened, almost mystical and supposedly more aware way of being in the world), perhaps radical pedagogy needs to admit an equally mystical temperance in approach.

To state the idea more clearly, I’m suggesting, as I again circle around my answer to “what’s my job?” that perhaps no matter how passionate, how ideal, how enlightened, how socially responsible a teaching approach aspires, if that approach does not acknowledge the students’ critical autonomy, their personal decision to engage or not engage the classroom and the world in whatever way they choose, it inevitably shifts from empowering to overpowering, from critical consciousness to critical indoctrination.

If education hopes to borrow the spiritually lofty goal of consciousness raising, maybe it needs to also borrow the common spiritual motif found in Zen and so many other mystical traditions of “when the student is ready the teacher will appear.”

Alchemically, then, my philosophy becomes a philosophy of calcinatio –the alchemical process of burning away of impurity, a burning away of personal ambition, of self-assuredness, a letting go—baptism by fire, as they say (5-5-2019).

In my first impression, something mysterious and just beyond my grasp has occurred in the space between the original window/mirror philosophy and this later, overly intellectual alchemical philosophy. Who was that swaggering twenty-something who tossed around the windows and mirrors metaphor of teaching with utter faith and embarrassing bravado? And the thirty-something who tried to buoy his fledgling determination with some overly intellectual alchemy construct? Have I fallen so far? From the alchemical to the administrative. What becomes of lofty visions of transformation when they are resigned to the book-keeping philosophy of education, the deskilled technician who keeps careful account of the points in Canvas?

In using these two iterations of philosophy, I offer a view, colored and refracted, of even a small measure of fragments that might constitute a relationship to the self and construction of a teaching identity. As I dialogue with my self across the page and throughout time, I hope to have rendered visible that which is invisible in my relationship to the institution and the rotating flecks of colored glass.

Naturally, to reflect requires an inward looking and yet I have had to both create this inner space for myself and within the PDP while also arguing for its importance and need within the structures of the institution. And so, with invisibility, comes invisible labor and invisible burden. We might wonder at who is rewarded and most supported in a PDP structure that doesn’t create space for the teaching self and asks candidates to measure their institutional visibility and ability to collaborate before and without considering or outlining the shape and contour of the self and the beliefs that they bring to the institution.

Ways of Seeing, Ways of Being

Questions about teaching must be more than questions about teaching; they must be questions about living, too” (Tremmel 11).

The other morning, sitting at my desk with my first bitter, black coffee, a copy of Thomas Merton’s Zen and the Birds of Appetite, and a dozen other books strewn haphazardly atop my desk, more nestled like ant piles in various other nooks and corners of my apartment, along with handfuls of notebooks half-scribbled, half-mad, I wondered at this visual display of my literacy practice. More simply, I wondered: what has all this been about? And I don’t mean in the librarian’s bumper sticker—reading is sexy, I stop for wildflowers kind of way. I mean, more, that some yearning or searching seems to underlie my reading and writing life. And that sounds sort of esoteric and lofty, and I guess it is.

At the same time, I consciously acknowledged something that I have always known: my reading life, its longing, its idiosyncrasy, part-philosophy, part-poetry, part-Zen, part-psychoanalytic, has always been about searching for a way of seeing the world. Against the whirlwinds and chaos of my inner and outer lives, I have turned to books, to reading, to the contemplative, for some orientation. For me, even before Freire, reading always served as a way to see the world, to construct worldviews out of shifting sands. And while that aspiration always feels incomplete, it also always feels worthwhile, comforting, and important.

Even more, these postures of seeing have, at their best, been in service of being. That is, my yearning for a way to understand, to think clearly about myself, our world, and others, has been in order to act in that world. And somewhere, out of my devotion to this concept lies my teaching practice.

In starting with the model of my own reading and writing life (seeing and being), I hope to offer students opportunities and experiences that allow for literacy to inform their seeing and that perhaps with enough patience and guidance they too might begin to connect that seeing with their being.

And so rather than “inspire students to create a better world”, a disembodied breathing into, I want to give students space to breathe for themselves, that they may one day read and write and breathe their own worldviews. From that breath, they might decide who or how they want to be.

In sum, the previous section of writing has required a steady gaze into the more theoretical, philosophical, and political dimensions of both a teaching life how that teaching life unfolds in a particular institution. I have attempted to identify and outline the places where the existing portfolio structure presented me with challenges, questions, absences, inconsistencies, or various other points of consideration. While no structure can account for every possible approach to professional reflexivity, I think the following final points are worth noting:

- In what way might the portfolio begin with a sphere of the teaching self, which would include philosophy, experiences, or space to otherwise broadly outline the beliefs, values, and theories (reflections) that inform or initiate a teaching practice? In this subtle revision, rather than starting with ‘executive functioning’ or ‘relational cultivation,’ or the implication that a candidate’s first purpose is to fit themselves within the social/professional milieu of the school, this shift will recognize, honor, and value the autonomy and primacy of the teacher as an individual and professional.

- Likewise, along with a teaching philosophy or a teaching narrative (this is a pretty common genre in pedagogical journals) this domain might also include an opportunity for the candidate to reflect on the activities, practices, and relationships that energize, nurture, or otherwise support their teaching life. In this, rather than trying to quantify the teacher as a ‘technician’, this domain might recognize that our profession requires and involves our selfhood in deeply personal and emotionally demanding ways. Here we might reward and recognize how our living practices are intimately interwoven with our professional practices.

- The relational/community membership sphere will expand to include an indicator about the ‘invisible ways’ in which a candidate participates or contributes to the school community. As mentioned, the existing model foregrounds and privileges certain gestures, modes, and professional personas but may not account for a wealth of invisible labor or other types of community engagement, contribution, etc.

- If the school can’t afford an entire course release to support the time and energy demands of reflection, gathering/analyzing data, and actually composing portfolio material, perhaps a few extra days of PDD, might offer candidates time, space, and dignity to meet the demands of genuine reflection with thoughtfulness and generosity.

Regarding the PDP process, amendments might include:

- The opportunity for development experiences outside of the school day, including workshops, classes, events, etc. This will both move the PDP experience beyond reflection and beyond the insularity of the immediate EPS community.

- Rather than moving candidates through the experience, in isolation, as the sole object of the committee gaze, the year might involve some moments where candidates can dialogue as a cohort or develop community through a shared PDP experience. This would eliminate the feeling of remoteness, isolation, and disconnectedness of the PDP abyss.

To momentarily conclude these meditations, I borrow a fishing metaphor: after fishing a particular hole as effectively and thoroughly as possible, a wise angler will take the approach of letting the hole rest, walking away so that that they might return later to ply its waters once more. Here too, for now, it’s time to let rest these waters.