4.

A Teaching Practice

“Thought without action is empty; action without thought is blind.”

-Kwame Nkurama

Building Classroom Culture/Community

Though I could begin again with the higher-level abstractions about community and the challenges of building the micro community of a classroom against and within larger school cultures and societal pressures, for this section, I want to begin in the opposite direction. That is, rather than theoretical reflection, I want to begin from within the practice of the classroom, ‘the midst’ of teaching, and students, and the living organism of adolescents and learning. In that spirit, I intend to turn to several sources of data and see what themes, patterns, and qualities emerge, letting the data inform the reflection.

For the first point of analysis, I want to examine a recent classroom discussion in the American Literature course. I have selected this class for how it extends previous reflections that surfaced during the writing on collaboration and for the potential ways in which it illuminates elements of a classroom culture, including peer-to-peer dynamics, cultural competence, inclusivity, student preparedness, engagement, and self-advocacy. Intuitively, as the discussion ensued, I sensed something valuable and authentic unfolding and so I spontaneously asked the class for permission to audio record their discussion.

Up to this point in the trimester, I would have characterized the classroom culture as idiosyncratic at best—some days, brief moments, and flashes of a community of learners. This particular class, however, stood out as a turning point or high-water mark in the quality and content of student engagement. Beyond academic excellence (our students are often technically excellent), students appeared genuinely interested in both their own relationship to themes of identity, authenticity, and performance and equally interested in the experiences and ideas of classmates.

The discussion in consideration came at the end of a sequence of lessons that I planned as a foundation for major thematic anchors in an African American literature unit and a prologue to the Harlem Renaissance. The texts students read, analyzed, and explored included important themes about double-consciousness, code-switching, and masking. Preparatory activities included an imitation poem of “We Wear the Mask” by Paul Laurence Dunbar, a guided reading of Dubois’s seminal essay on double-consciousness, and a group activity where students selected one of four short stories to examine for these themes (“Big Black Good Man” by Richard Wright, “Drenched in Light” by Zora Neale Hurston”, “How it Feels to be Colored Me” by Zora Neale Hurston, and “The Girl who Wouldn’t Sing” by Kit Yuen Quan).

I note the preceding, to account for how the discussion in review fits within a broader curricular arc and to possibly account for the foundations which supported and allowed for the depth and dexterity of student engagement. As a primary consideration, I would like to examine the layers of thinking that inform the process of text selection for a successful lesson.

Setting the Table: On Text Selection

One scholar (Kumaravadivelu, 2001), identifies the dynamism of forces that constitute a classroom and the need to respond to the specificity of those forces as “pedagogy of particularity,” which claims:

language pedagogy, to be relevant, must be sensitive to a particular group of teachers teaching a particular group of learners pursuing a particular set of goals within a particular institutional context embedded in a particular sociocultural milieu. (p. 538)

To further outline and identify the elements of design and overall breadth of considerations involved in curriculum development in the English classroom, I want to note a few particularities about the selections above.

While all classes certainly include discipline-specific considerations, the English classroom exists as a unique space that inherently surfaces and troubles our deepest notions about the ideas, experiences, and beliefs most intimately connected to notions of our humanness. In addition to this innate connection between language, story, and humanity, the sheer possibility for curriculum arrangement creates an almost limitless number of outcomes.

Not only do texts change from year to year, even an anchor text becomes altogether different depending on numerous highly personal, highly variable decisions. Where curricula in certain disciplines may remain static, largely unchanged, and governed by rules, laws, or formula (the periodic table, for instance), curricula in the English classroom are like proverbial streams, never stepped in twice the same.

For example, at the international boarding school where I formerly taught, I included Sherman Alexie’s Absolutely True Diary of a Part-time Indian as a central text in a classroom of English Language Learners (ELL’s). Alexie’s crass humor, the young adult reading level, the illustrations, the thematic connections to literacy, identity formation, and adolescent love utterly transformed my classroom. Before my eyes, classes of reluctant learners, struggling readers, and somewhat despondent young people suddenly came alive with enthusiasm and levity. Ultimately, I attribute this success to the subtle particularity of the right text for the right group of students.

When I arrived at EPS, to Washington, only hours from Alexie’s hometown, I would have considered him a top candidate for an Indigenous author to tether a native writers unit in American Literature. Unfortunately, in 2018 accusations about Alexie’s inappropriate sexual conduct began to surface. Suddenly, an author and text which had succeeded tremendously in one context, might have been quite harmful in light of new information about an author’s personal life.

Last year, in the middle of a feminist poetry unit seemingly poised to center women’s voices in a traditionally male-dominated cannon, a student researching the poet Anne Sexton discovered that she had allegedly abused her daughter. Suddenly the poem, which seemed to convey a tender dialogue between mother and daughter, “My Little Girl, My String Bean, My Lovely Woman” acquired an entirely different meaning. That poem, read at an anti-Vietnam war demonstration, formerly a testament to the ‘personal as political’ as a justified and even necessary alternative to patriarchy, becomes something new, even creepy. The words on the page utterly unchanged, the same arrangements of letters and punctuation marks, suddenly transforms with haunting discomfort.

Just as meaning in language depends on a chain of signification (the relationships between words determines meaning), texts are also situated within cultural, historical, and artistic chains of signification. Not only are relationships between signifiers subject to the vicissitudes of history, culture, and current events, they are highly politicized, contested, and tangled-up in a web of particularities. Furthermore, text selections, assignments, and each component of the English classroom opens a flood of subjective beliefs—from state school boards banning curricula to parents who blame Sylvia Plath and Ariel for their child’s late-semester academic slide.

I might add another dozen examples similar to those mentioned above. All to say, the delicacy and nuance of a successful constellation of texts, lesson sequencing, and creating the overall classroom culture for a lesson like the one above, requires deep roots of practice. At the behest of my committee, I have attempted to more explicitly demonstrate my role in the intricacies of lesson designing. In truth, this process, the task of situating oneself within the breathing organism of the English classroom deepens and complicates further still.

As with any discipline, to teach the content mentioned above (Hurston, Wright, Quan), requires certain definite, objective knowledge and expertise. However, where the STEM disciplines allow a teacher to maintain an objective, quantitative relationship to the content, with literature and language, the content always also requires a qualitative investment.

That means, to create a learning experience for students around the themes of masking and double-consciousness as they are embedded in a Black experience, I must have engaged these texts on a highly personal level, wrestled with my own identity position as a white, middle class, cis-gendered man. In other words, the core of my being is also always bound up in the network of students, texts, and world.

In the case of the lesson in review, the planning did not begin the night before or even the year before, it began over a decade before, when I enrolled in the African American literature class where I read many of these texts and authors for the first time. Through a series of courses and inspiring professors, I began a journey towards critical consciousness.

To conclude, as I write from within the midst of my portfolio process, I am reminded of how often, as English teachers, we wander the mists of unimaginable ambiguity and ambivalence. The very reasons which make art, literature, and poetry the essential languages that both emerge from and speak to the fleeting, fragmented, misfitted, troubled, wonderful world, make the English classroom a space of both tremendous possibility and urgent responsibility.

Peers in Authentic Dialogue[1]

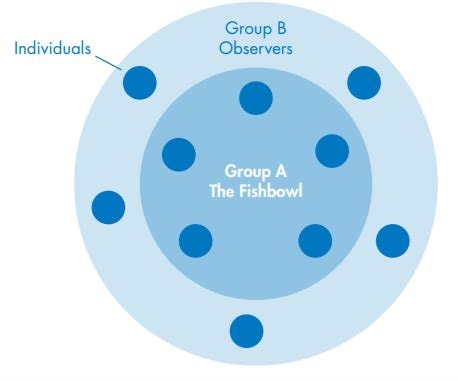

For the discussion in review, I experimented with a mini-fishbowl structure—half of the class in the center, managing a discussion, and turn-taking, while an outside partner took notes on a single classmate’s comments and contributions. This allowed for more intimate, vibrant discussion in the inner circle, with attentiveness and engagement from the outer circle. For this fishbowl, and as often as possible during other informal student discussion, I sat among students, in the inner circle. I prefer this seat for my own comfort and for the way it embodies a horizontality. I also have a visceral skepticism towards podiums. To frequently sit at the same height as students, eye-level, at various table groups allows for a seemingly inconsequential but highly significant shift in the effort to distribute power, allowing students more opportunities to center their knowledge, learning, and autonomy. For clarity, I have included a diagram of the mini-fishbowl below:

I would like to credit Jen Oakes for the design of this particular capstone activity. Jen maintains a constant eye towards opportunities for students to think about course themes, concepts, and readings in their own lives and in contemporary society. Here, we asked students to create “visual piece (an artifact, artwork, display, etc.) that helps to make clear the concept of double-consciousness, mask-wearing, or code-switching (choose one) and some of the ways this idea is still relevant in the present day” (see appendix for more assignment details).

In these student responses, I hope to highlight the following characteristics of student engagement: extreme reflexivity, the courage to explore deeply personal aspects of identity, and the ability to use the assignment to circle back to highly sophisticated course readings and concepts.

After a long preface about a childhood experience of starting at a new school as the only student of color [2] and atheist in a predominantly white and Christian-based school, a student poses a question to the fishbowl group trying to make sense of their experience of acceptance and assimilation.

Student 1: And I was thinking. I was very accepted, but was this acceptance the result of me crossing the veil? As you know, as W.E.B. Du Bois says in, you know, Strivings, right? Did I cross the veil and succeed in this other world? Or, in a more interpretation based on Zora Neale Hurston’s ideas, was this just me being authentic, and just people sort of accepting it? And I was only brown, or different, or atheist, when just put against this background. This background of white, of like, mainly white people, uh, more Christian basis. Was that really the difference, just the contrast of just being around there? Or was there an actual difference of an effort put forth by me to change?

Student 2: Well, I think regarding your question about if it’s crossing the veil, or if it’s connecting to Hurston’s idea, I think, because you said they accepted you, and sort of, even though you felt, like, different, maybe, like, they still accepted you, and you didn’t really have much pushback, I guess, going into that, right? Um, I don’t think it’s mostly, like, crossing the veil.

Du Bois, I think, is expressing, like, an idea, right? Like, you’re gonna experience a lot of pushback once you cross that veil into the white society and so you need to, like, you need to not only conform to that, but you also have to take all that, right? But I think you did sort of conform, but you didn’t feel that pushback, so I don’t, I don’t think it really connects too much to the veil.

Student 3: I think it would say that you were being your authentic self and you realized that, um, that contrast, maybe, and then you wanted to do your own thing. Maybe separate yourself from that. Um, yeah, I agree with what (Student 2) said, and also I agree that it’s not really what Du Bois is saying, because with double consciousness a lot of times you have to sacrifice one part of your identity to conform to another, and I don’t think you had to do that in this case. I think they just kind of accepted the fact, like, accepted your differences and then that was it.

In addition to the keen treatment of some notoriously difficult concepts that inform this unit on African American literature, a few other notable moments arise in this opening remark. Firstly, Dubois describes a unique form of racial consciousness that results from being a Black man in white supremacist society—the split in consciousness in trying to reconcile both American-ness and blackness. Here, in the candor of their childhood anecdote, Student 1 reaches across gulfs of time, identity, and whatever other cultural/racial/political divides in order to think seriously about the Black experience. Even more, they use their reading as a vehicle to explore moments of their own dividedness or othered-ness.

Along with the ability for students to traverse with Dubois these immensely difficult terrains, I marvel at the maturity and risk-taking for a student to share artwork, a vulnerable act in itself, that so intimately conveys an obviously impactful, lived experience. With this example, learning becomes grounded in the self-in-the-world. In sharing this story, Student 1 opens themselves to their classmates. Likewise, they open themselves to the experiences of Dubois—experiences outside of their immediate identity position. These various openings, made possible through the mediums of the student-created artwork, the texts in consideration, and a student-driven dialogue, creates a weaving of connections.

Through their spirit of curiosity, openness, and collaboration, Student 1 invites classmates into a shared inquiry. Just as the assignment and course readings became an initial invitation in crossing boundaries, Student 1 extends and expands that boundary crossing to classmates. From here, the discussion ripples and webs outward and inward.

In response to the opening question, both of the responding students offer thoughtful, well-reasoned, and tactful challenges and disagreements to the proposition, mobilizing their subtle readings of Dubois and Student 1’s anecdote.

For Student 2, the lack of “pushback” precludes the experience as truly crossing the veil. In a similar response, Student 3 notes that the lack of “sacrifice” presents an important difference. In both cases, responding students feel comfortable, empowered, and safe enough to pursue shared inquiry and discourse. By all accounts, students have ‘unmasked’ themselves, even briefly, for one another. The entire conversation offers a view of students embedded in courageous explorations of themselves and their worlds in a community of scholars.

Unmasking: Beyond Pedagogical Effectiveness

Both American Literature sections continued at the same soaring heights of dialogue, cooperation, authenticity, and connections to the unit of study. For the opening of the next class section, a normally shy[3] student spoke with incredible clarity and precision regarding the theme of masking in their own life:

Student 4: Okay, so to talk about masking, I made a literal mask to represent the facets of my life and how I hold this mask in my life. I usually like to represent my true self and my genuine self, but I like to talk mainly about the outer layers of myself and I hide the insides of the mask.

You might actually not be able to see this, but in the inside, there’s my deepest insecurities and fears and then it’s layered by personal activities that I do that I don’t share with anybody and then only slowly and slowly you can build and you can see on the outside, you can only see me smiling and you can only see me at the bridge table and the things that I always frequently talk about. I think this is in many ways similar to the poem that we read, “We Wear the Mask” by Dunbar. I think it really connects, but it’s in a different way because I mask and I still show, I think I show parts of my identity, but I selectively choose it.

I’m not giving a false, I’m not hiding my pain. I’m not hiding myself. I’m just choosing to select different parts of myself for college, but I’m not purposely trying to change or deceive anybody.

Of course, I’m not facing the same oppression that Dunbar experiences and to conform to society, I just choose to represent different parts of myself and show the outer parts of my mask.

In re-reading this student’s spoken description of their work and the way they used their created visual to interrogate the act of masking or un-masking in their life, I am humbled and daunted. I am humbled to witness a student and young person speak so bravely to their “deepest fears and insecurities” among a group of peers. Moreover, I am humbled at Dunbar’s poem, and the power of his careful arrangement of meter and rhyme and the mastery and tenacity it took to capture his experiences, through poetry, in a way that still reaches across time to the heart and being of a young person seemingly worlds away, and yet incredibly near.

And I am daunted. Even this tiny spark of classroom discourse, less than a minute of speech, contains a lightning strike of insight, surging, electric, and awesome. How to begin to catalogue or situate these flickerings and flashes of student magic and what does it mean to try to lay on top the breathing organism of the classroom the dead weight of a weird schema of ‘pedagogical effectiveness.’

In their response to the previous student’s explanation of masking, or choosing to show certain parts, an interested and engaged peer (Student 5) inquired:

Student 5: I had some questions, or a question really. For you two, especially. Do you feel a pain in masking, or is it something that is almost a survival mechanism? Is it something that you do by choice and you’re fine with that choice of doing it? Or is there a part of you that maybe wishes you could show everything?

To which, the opening student responds:

Student 4: I feel like it’s kind of a bit like survival, and I feel like it’s fine. I feel happy with my choices because, of course, with a more… I talk about this in my artist statement, but with a closer circle and more people that I trust, and people that I know better, I might share more deeper and deeper into the mask.

I think, in part, to use the languages of this lesson, and the model of students sharing in earnest, what I have hoped to do with my portfolio writing equates to a type of un-masking and a hope to think “deeper and deeper into the mask.” To capture a teaching practice requires an unmasking, and maybe this writing is an invitation likewise for anyone else who might be interested in that type of dialogue.

At so many different points in the compilation of my writing, the question of audience continually arose—who is this writing for? In their incredible dialogue on masking, my students have helped me clarify an answer to that question. My portfolio audience is anyone else who has the courage or care to sit and share, who wants to take off their masks and think carefully about what we do as educators, what we care about, and what shape the school might take in the coming years.

The student who initially asked about the “pain in masking” moved into a discussion of their own work:

Student 5: Oh, I was just going to connect it to my piece, which is kind of like a meditation on the connection in our society between whiteness and femininity. Feminine beauty is very much connected to whiteness, and that is a big reason why I felt like I needed to mask through my life. It’s because, I don’t know, I feel like as a brown person who’s not black but is brown, I have a proximity to whiteness, which makes it complicated for me because growing up in white spaces, I was able to sort of get in with the white people rather than being grouped with the darker brown or black people. So that really affected how I see myself, because I kind of saw myself as white, strangely. But then the people around me didn’t see me as white.

Student 6: Did you see that as more masking, like you still had a true and inner self, or was it more like code switching where you were being indoctrinated or indoctrinating yourself?

Student 5: Yeah, I think it was very much like self-delusion kind of thing. The way that Du Bois talks about double consciousness, I did not have that double consciousness. I instead, the lack of my double consciousness was excluding me from seeing how other people saw me, and so I was kind of stuck in that childlike state of thinking that I fit in with everyone else.

The student who offers this disarming reflection about societal connections between whiteness and beauty and their own precarious understanding of that strange matrix, brings up a final point that I hope to emphasize. Without spiraling too far afield with apocalyptic lament, in the contemporary moment dominated by empty, superficial spectacle, and an endless, unceasing barrage of hollowness and whatever other cultural malaise you might conjure, this student speaks to something utterly essential, fundamental, and worthwhile.

Because of the hard-won experiences and long tradition of feminist writers and courageous women who took the personal as political, who used art and poetry and educational and informal spaces across the world to assert themselves against patriarchy, this young student inhabits a safe classroom space in which she might grow down into her own inner depths and contradictions.

In truth, for this class, I am not sure if I (designed, brought, began, concluded, coached, adapted, ensured, developed, or considered) anything with any degree of ‘effectiveness.’ I did get to witness and share, and maybe steward something special that happens when people gather around language and sieve up their humanity in poetry and art and community. At the same time, in clearing that space, in setting the table, in tending to the lights, in arranging the seats, in setting a vision for how we might come together and for what purpose, I do take responsibility. And yet, I can’t imagine how I might quantify or even communicate that, other than trying to bring my own practice and care for literature and the power for writing and reading in my own life and hold that up for students and to celebrate them when they take the time or energy to do likewise.

While I don’t think I can take much credit, quantify, or calculate exactly how a moment like this happens in the English classroom, but I know that in my career, and in my commitment to both literature and writing instruction, and when all the stars of classroom magic align, I have witnessed moments like these over and over.

And that fills me with great pride and hope, but also a sneaking splinter of despair. I despair to think that rather than expanding and holding up these moments for their preciousness, they are getting lost, overlooked, devalued, and obscured by the grinding gears of some terrible machine. The quiet and care and gentleness are swept aside for the frantic pace and lock step of some other purpose.

If anything, I’m not worried about whether my lessons or my classroom community meets the criteria of a PDP One Note, I am worried that one notes, and PDP’s, and other institutional structures do not rise to the occasion or create space for lightning strikes of students who read and write and care.

“The Indignity of Speaking for Others” -Foucault

I would like to add a brief conclusion to the preceding section. While I intended to use this view of the classroom because to me it demonstrated the intersections of a few deeply complicated aspects of teaching at once: curriculum development, the ways in which identity and difficult themes constantly shape the literature classroom, and what I thought captured students’ ability to engage in a learning experience with genuine care and investment.

At the same time, I acknowledge the ways in which as researcher and author of the researcher text, my writing, my beliefs, and my presentation of the data have presented a highly subjective and narrow interpretation of both the lesson and the students’ experiences. To balance these unavoidable biases and to broaden the scope of the research text, I offered my draft to four of the participants for feedback with the following email:

You may recall from waaaaay back before the new year, we worked on our ‘masking’ projects. At that time, I collected some data (recording the conversation) that I have used in part of my professional development portfolio. In brief, this section was meant to explore some of the criteria around ‘classroom culture’, ‘designing lessons’, ‘engagement’, etc. I was hoping to add a layer by letting you, the participants, read, reflect, and maybe sit down for a conversation about the research text included here.

You could:

- Reflect on the way the lesson or student engagement are represented in the text.

- I would love to hear any comments about if this constitutes a moment of genuine engagement, what are the elements that encourage or allow that (relationships, material, teacher).

- Anything else you want to share/have questions about.

This is a bit long—if you want to skip some of the background context, the meat and potatoes picks up around the section “Peers in Authentic Dialogue.”

Thanks for your consideration. If you are too busy, no worries. If you are interested in a 15-20 minute debrief with your peers, shoot me a note.

-JL

With the demands of the school year and frankly my own waning capacity to undertake the material demands (time/labor) and the emotional demands of looking seriously at the classroom and the student experience, I amended this to a request for written feedback.

After I sent this email, during an in-person conversation, Student 4 sort of hinted that student responses to the discussion might not actually align with my interpretation. In a timid preface they said, “we don’t want to hurt your feelings.” Initially, I imagined that this comment implied that the discussion did not in fact contain any of the lofty elements of self-searching and splendor as I portrayed. In my most cynical musing, I suspected that the student would reduce this activity to its barest bones: a grade. In their email response, they somewhat confirmed my suspicions, noting that they were,

[I was] kind of scared of this discussion, everyone cares a lot about their grade, so they feel obligated to do this since they think their grade might be impacted. Grades are a strong motivator for discussion, though it may not always be the best approach – definitely depends on students, works decently well in this class (email 5-2-24).

Alas, we cannot escape the shadow of the grade. In the same email, Student 4 adds an additional skepticism:

I do have [one] thing that I think you might find interesting about my overall takeaways with conversations with others mentioned in this discussion about the fishbowl.

I appreciate your engagement with us outside of class and thinking about this, but we were a bit confused why this was the central theme of your professional development. We were pretty shocked that you shared with us your insights and personal stuff since we didn’t really know much about you, but we also were a bit confused about what you were impressed about. Were you impressed of the engagement of the whole class or the complexity and deepness of the topics we discussed? We thought that a fishbowl discussion was just a certain type of discussion, and that this one wasn’t much better or worse in quality than other discussion that we have had in other classes.

Here Student 4 expresses doubt about any exceptional quality to the fishbowl discussion. Where I proclaimed the heights and depths of student achievement, they felt less obviously impressed. To my credit, I might add that perhaps students are not always the best measure of their own achievement. At the same time, I find a tendency for students to resist the possibility of recognizing deeper meaning in their work because they want to stay entrenched in the role/persona of victims of the system in which authentic engagement becomes thwarted by the tyranny of grading and assessment. In some way, by having grades as a scapegoat, students do not have to take responsibility for their learning.

In their email response, Student 1 notes, “So I did a fairly detailed read-through of the document – and I thought it was really cool! I think it was a pretty cool representation of our discussion from your perspective” (email 4-28-24). I would draw attention to the gentle qualifier at the end of their enthusiasm: your perspective. In my relationship to this student, and knowing their disposition, I read the understatement to suggest that my perspective does not fully account for the forces at work in the discussion, which it certainly does not.

Without writing too deeply here, I end with a pair of reflections on this point. I have preserved the interpretation of the fishbowl in its original form to capture my idealism and naivete about the nature of students’ attitudes towards their learning. Much more serious research is required to gain real clarity here. Likewise, completing a professional development portfolio without more robust and active engagement/representation of students in my classes is a sort of disconnected exercise in self-aggrandizement.

To truly work towards a deeper understanding of practice would necessitate more time to actually conduct qualitative research like the example above and the will to confront and unsettle easy assumptions about ourselves, the classroom, and our students. In other words, the portfolios can persist in totally teacher/administrator dominated incubators or they could begin to open more intentionally to include student voices and in-depth research approaches.

[1] I would add “Peers (In) Authentic Dialogue” as an alternate title to trouble the notions of perceived authenticity.

[2] “Although my art piece is related to concepts of “crossing the veil” and double consciousness which are applicable to a wide variety of cultural backgrounds, I just would like to be sure that it was made clear that my empathizing/connection with Strivings in that discussion is not because I am a BIPOC student rooted in the cultural background and history that Du Bois references, but rather simply a non-white student who connects with broader themes of the work. I think that having that distinction made slightly clearer (e.g., by stating that Student 1 was of Indian descent) would make my contribution/relation to the discussion way clearer!” (Student 1, Personal email 4-28-24).

[3] In a personal email Student 4 wanted to clarify that they are not ‘shy’ but felt others had already shared what they wanted to share, that they had some fear about being judged for comments, and that they feel more comfortable in one-on-one conversations (5-2-24).